I stood at the entrance to Basma alSharif’s A Philistine exhibition at the Centre for Contemporary Arts (CCA) in Glasgow. The stark modern black and white design of the show poster and entrance typography contrasted with the warm glow and cosy exoticism of the first gallery space peaking through the doorway.

It was styled as a fictional Oriental divan room – low-set sitting area formed by mattresses laid against the perimeter of the room with cushions to lean against, decorative fabric draperies on the walls, a large coffee table in the middle and two chairs.

There was silence around, so I didn’t want to interrupt the ambience by clicking the shutter of my camera. Quite a number of visitors reclined on the divans, reading or leafing through a little book with a bright yellow cover.

The room’s furnishings, the book and the people themselves were part of the installation, a sort of prologue and a metaphor for the show. As alSharif, artist of Palestinian origin born in 1983 in Kuwait and raised in France, the US and Gaza Strip, said in her interview to The Skinny,

I had been thinking for a long time that I really wanted to do a work centred around a text that I wrote, and that the exhibition itself would be a reading space for this book essentially.

The text in question is Basma alSharif’s novella A Philistine (2018) that gave the name to the show. Written in English and translated into a Palestinian dialect of Arabic, the novella bears traits of a travelogue, science fiction and erotic fantasy.

It tells a story of a young woman (Loza) on an imaginary train journey moving backwards in time, from present-day Lebanon, through 1935 Palestine and ending in New Kingdom Egypt (16th-11th century B.C.) on which the main character encounters mythical creatures and rituals. The train route itself is a fictional re-invention of the now defunct Palestinian Railways and the Haifa-Beirut-Tripoli line, imagining the journey without the presently existent borders.

Introducing a reading group hosted as part of the exhibition, the artist wrotes,

Since this work deals with seemingly irreversible borders of colonialism, I wanted the work itself to be an exercise that happens in a shared physical communal space, reading an allegorical text that attempts to undo what has become the highly fractured landscape of the Middle East and North Africa.

A Philistine: Reading Group hosted by Basma alSharif, CCA, 2019.

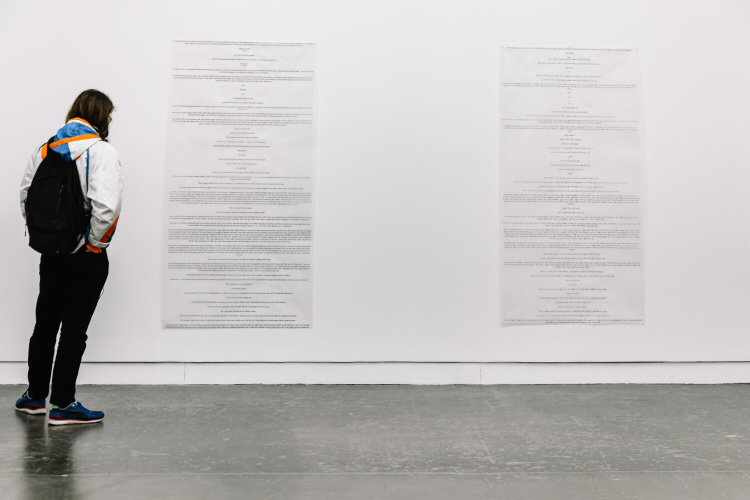

The gallery space adjoining the “reading room” continued to unravel stereotypes about Middle Eastern identities, histories and geographies. The two rows of oversized photographic banners suspended from the ceiling led the eye to the walls where the vertical paper strips/scrolls with an excerpt from A Philistine was presented in English and vernacular Arabic. All the while the visitor could hear an audio-track of a soft female voice reading from the novella in Arabic.

In the featured fragment Loza steps out of the train to take some air and, as her train leaves unexpectedly, finds herself stranded in the 1935 Gaza, without her passport, phone, money and clothes, unable to contact anyone she knows, possessing only her mother’s broken Arabic language.

The town seems untouched by the 30s political turmoil. Couples and families stroll leisurely near the sea in the Port of Gaza. As the sun goes down she cries, lost, helpless and famished from her ordeal, and the palm tree suddenly lowers itself to offer her some dates. A mysterious local woman conjures up some camel blankets for her to sleep on. Passing by horses ask her if she needs anything. 100 Years of Solitude alSharif’s way…

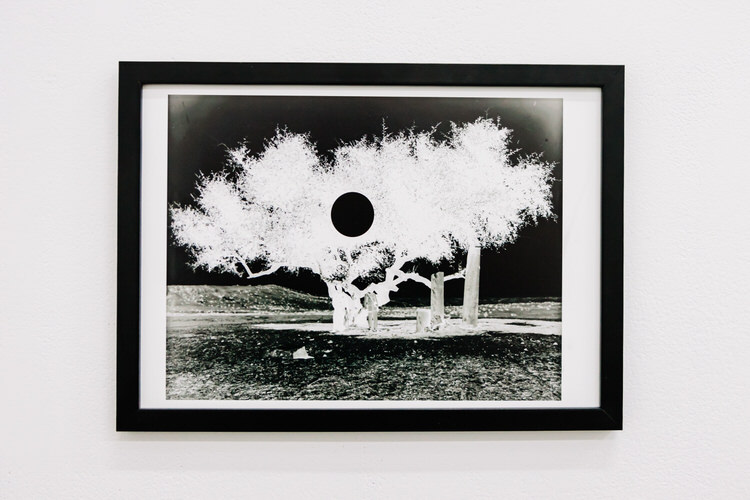

The subjective story of Loza’s mysterious and bewildering encounters revealed in the paper scroll enters into a contextual dialogue with a series of the framed black and white prints on the walls. We are presented with a selection of traditional photographs of Middle East from digital archives, taken by Western travellers or ethnographers – stereographs of local villages, majestic air views of the river Jordan and the sea line, vast arid desert landscapes and a portrait of a girl in Palestinian costume.

In Saidian terms (Edward Said, Orientalism (1978)), these images reproduce exotic Orientalist tropes in the service of colonial powers, systematic (mis)representations of the Middle East as the passive “Other” to be “administered” and mastered. The dot, digitally added to each the framed prints, is a warning that they are not to be consumed at a face value as faithfully reproducing some impartial or factual reality, but as part of the installation.

Functioning as “exhibits” displayed on the gallery walls, their status is strengthened by uniform framing. However, none of the prints have any descriptions, attributions or legends attached to them bluntly circumventing the issues of authorship and provenance. The artist herself admits that her extensive use of archive materials taken by Westerners “to various degree of the copyright infringement” is almost a political gesture, an “insistence”:

I feel like there is something [of interest] about bluntly reappropriating these images and getting to decide how they function, regardless of whether or not it is right or legal. Because to me what happened previously is neither right or legal.

Katie Dibb, Artist Basma Alsharif Reimagines the Middle East, The Skinny, 1 Nov 2019.

Furthermore, the same images are duplicated as negatives, on the one hand, disrupting the unquestioning viewership process, and, on the other, drawing us into the mysteriously transformed otherworldly spaces filled with irrationality – just as Loza is drawn into and tries to make sense of her disorienting 1935 Gaza experiences in A Philistine novella.

A mildly dysfunctional photographic scene from the Library of Congress digital archives representing a local and an enthusiastic Western “explorer” under an old olive tree heroically posing next to some ruins amidst the wilderness seized my attention. When transformed into a negative, the print suddenly loses its legibility and invites more deliberate scrutiny .

Is this transformation from a positive print into a negative a step back in time or a step forward beyond the spectre of colonialism to the new, more creative ways of engaging with tropes? After all, moving back to move forward is a premise of the novella and an artistic method alSharif repeatedly employs in her work across different media, as Chris Sharratt observes at the outset of his Art Agenda review of the CCA exhibition.

I find it intellectually curious that the photographic banners in colour, so prominently placed in the middle of the gallery, seemingly have nothing to do with Palestine. There is a giant snapshot of a building in Belgrade from a train window, an ornate Neo-classical architectural facade, an indoor planter in a modern foyer that could be anywhere, fragments of interiors, a red armchair, together with a some-place minaret tower against a blue sky. Yet the framed monochrome prints on the periphery are overtly themed as Middle Eastern.

In fact, alSharif active extends her imagery beyond the Palestinian past or present to embrace the human condition. The traumas Palestinians carry in themselves, cruelties of war, injustice of the land taken from your people and “administered” away, the narratives of dislocation and exile, nostalgic memories of the past had been, were, and are being dealt with by other people, in other places. The artist shares in her interview to The White Review,

… my hope shifted away from Palestine, … and towards connecting it to other histories I saw Palestine reflected in.

Through my lens I saw the importance of the vantage point in experiencing the installation. The dominant central viewing position favours the banner and the text scrolls, effectively removing the black and white prints from sight. Similarly, spectators have to turn their backs on the hanging banners in order to scrutinise the framed images. One has to be willing to purposefully change their perspective in order to include both.

I only peaked into the screening room with a two-seater sofa, where three of Basra’s short films – Home Movie Gaza (2013), Further Than The Eye Can See (2012) and Rennie’s Room (2012) – were looped. The films re-played some of the motifs of the novella and the installation, such as moving backward in time, mystical characters fictional landscapes.

I entered the projection room when Home Movie Gaza was playing but couldn’t appreciate its story of the Gaza Strip rooted in a complex and fragmented everyday life against all odds because my eyes started hurting from the quick-changing footage. I turned away from the screen to meet the eyes of a dad and his daughter visiting alSharif’s show.