One sunny day in June 2014 I stood with my camera in the middle of Friars Vennel, Dumfries, staring at the row of colourfully painted houses whose façades were decorated by trompe l’oeil murals. There they were – an illusionary Paws to Buy pet shop, Gifts and Accessories and Byre Antiques, aligned seamlessly with to Moserleys, a still working award-winning butchers shop.

A woman came out of the real pets shop, Pets Paradise, on the opposite side of the street, poured water to a dog tied outside the entrance and approached me quietly. ‘You really must take some pictures of these paintings now because in two weeks the houses are due to be demolished’, she said.

Indeed, within a fortnight the buildings at 51-61 Friars Vennel, perhaps the oldest in Dumfries and defining the appearance of the historic Dumfries town centre, were demolished. The much-discussed demolition proceeded, despite multiple petitions and letters of objection from historic societies and public bodies and amidst accusations of vandalism and corruption. Many, however, welcomed the disappearance of the ‘site of shame’.

As a newcomer to Dumfries I felt ambivalent about this. An art historian in me mourned that the houses, full of character, were left derelict and decaying for decades,and no attempts of repair or restoration were made until it was too late. I also missed the colourful street art pieces that were gone too. Painted on the cheap pressed wood boards by Southerness artist Jo McSkimming, they were designed to be ephemeral from the outstart. The boarded up properties made the street look run down and it affected tourism and existing businesses in the vicinity. The local Traders Association welcomed the fictional retail townscape to disguise the problem and to highlight the historic use of Friars Vennel for trade.

On the other hand, the rationalist in me thought that surely some real residents buying real produce with real money would serve Friars Vennel and Dumfries better than attractive trompe l’oeils.

However, almost a year and a half later Moseleys stands next to a huge gaping hole left in the ground in place of the hastily destroyed buildings. There is no sign of on-going construction work… And no more ephemeral mural extravaganza that crafted the Friars Vennel experience as an active and thriving shopping location…

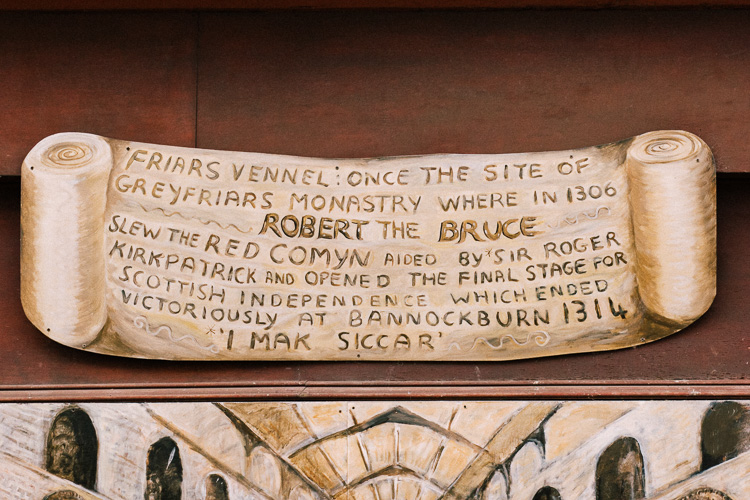

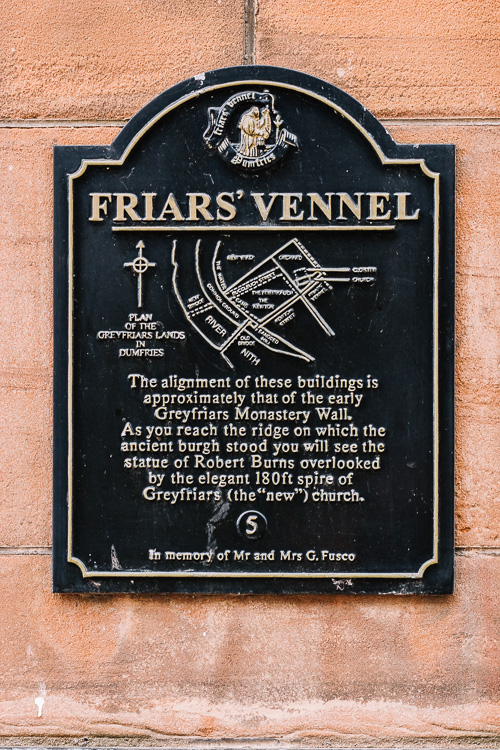

No doubt, Friars Vennel holds its important place as a stage of principal events in Scottish history. Here in the 9th-10th century Scots-Irish colonists pass after crossing the ford across the river Nith. Here, at the bottom of the street, the first wooden bridge was built to connect Galloway and Nithsdale. Here, at the top of the Vennel Lady Devorgilla founded Greyfriars Monastery, where later Robert the Bruce, a claimant to the Scottish throne, killed his rival John ‘Red’ Comyn. Here monks’ apple orchards blossomed in spring and here, just nearby, their breweries stood.

Yet, no historical structures are in situ now. Time was not kind to Friars Vennel. It was burnt during the raging plague epidemic on purpose. In 1702 it was burned to the ground accidentally. It was built and rebuilt, destroyed and resurrected. In fact, nowadays the whole street is a trompe l’oeil where historical references are carefully recreated. The faux medieval Ye Olde Friars Vaults pub hints at the old brewery trade. Multiple signs remind residents and visitors that nearly every building stands here on a historical site.

In the advent of the Scottish independence referendum Jo McSkimming’s mural I Mak Siccar on the boarded façade of another closed shop elevates the whole Friars Vennel to a site where the final stage of the 14th century victorious campaign for the Scottish Independence was opened.

Of course, the street painting’s location was arbitrarily dictated by the location of a conveniently neglected property to paint on, now performing a function of an outdoor museum. In fact, Comyn’s end happened closer to the higher end of the street. But the mural curates history in a fictional way, drawing parallels between the past and present strive for the Scottish Independence.

The absence of original edifices doesn’t mean the discarded history. The Vennel has become a repository of the cultural memory of Dumfries.

I fell in love with this complex location and used Friars Vennel in part for at least four of my Urban Portraits Dumfries project sessions so far. I am going to write about how I played with the cultural marker in my portraits in a couple of upcoming project posts. Bye for now!